The Free Black Women’s Library in Bedford-Stuyvesant occupies a narrow storefront on Marcus Garvey Boulevard. Inside, a poster of a woman reading greets visitors at the entrance. The walls are lined with shelves overflowing with books by Black women and queer authors. Some visitors chat and laugh, others knit or read quietly, while a few step out into the herbal garden in the back.

At first glance, it looks like a neighborhood library, with books organized by genre. But a closer look reveals banned or challenged titles occupying the shelves.

Founded to center Black women writers and bring their “influence, brilliance, creativity and diversity into conversations,” according to founder OlaRonke Akinmowo, the library has taken on new urgency as books by Black and LGBTQ+ authors are increasingly challenged across the United States. As school and university libraries take books off their shelves, community libraries like this one serve as counter-spaces – preserving access to titles that may be restricted elsewhere.

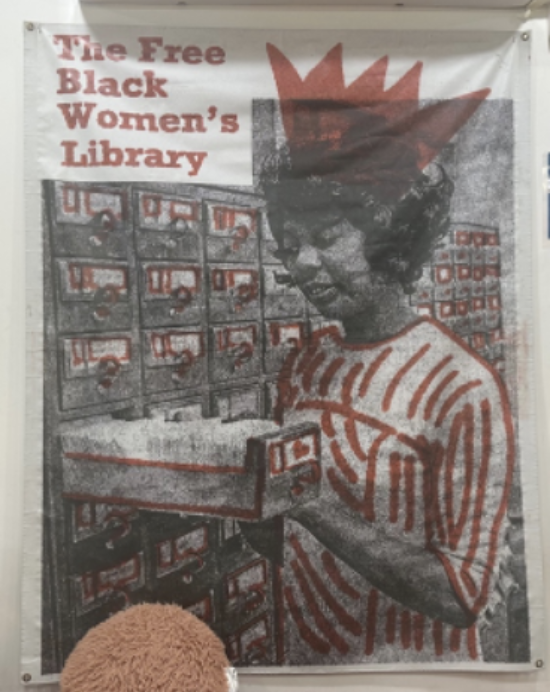

[To the left is a picture of the poster at the entrance of the library. Photo Credits: Muskaan Shah]

“Censorship suggests that conversations about identity, race, gender, and sexuality are dangerous,” said Sam Helmick, President of the American Library Association.

In January 2025, federal and state efforts to eliminate Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) programs led to the removal of more than 500 books from Department of Defense schools, according to a PEN America article. Many of these books addressed transgender identity, racism, feminism and democracy.

After operating as a traveling pop-up across New York City, The Free Black Women’s Library found a permanent home in Bed-Stuy in 2021 as its collection grew.

In response to shrinking access to books and declining youth engagement, Akinmowo is planning a new book club for neighborhood teenagers. She has been reaching out to local middle and high schools to invite students ages 13 to 17 to meet weekly at the library to read and discuss young adult fiction.

Efforts such as these are most relevant right now, when educators say that students must be free to choose what to read – including banned titles – to increase engagement. A National Assessment of Educational Progress report showed that reading scores in eighth graders dropped by two points in 2024 in comparison to 2022.

Despite the stagnant reading scores since 1992, “the current effort is historically unprecedented,” said Professor Harvey Graff, a historian and literacy scholar at Ohio State University.

According to Helmick, 72% of book banning requests come from special interest groups rather than local parents or educators. One of the most popular is Moms For Liberty, which Graff said often targets books based on authors’ race, gender and subject matter rather than actual content.

A 2022 article by PEN America stated that 42% of the banned titles contained protagonists or prominent characters of color, 22% directly addressed issues of racism and 33% addressed LGBTQ+ themes.

For Akinmowo, The Free Black Women’s Library is a way of saying, “We’re still here. We’re taking up space. We’re allowed to take up space.”

[To the right is OlaRonke Akinmowo, the founder of The Free Black Women’s Library. Photo Credit: Muskaan Shah]

Graff said that most censorship is based on belief and power. While the First Amendment protects people’s rights to access information, the states’ Departments of Education create and pass bills for book bans. Books can be unbanned by challenging the State Law Bill, but the damage is already done – access is already diminished.

However, some users of the library don’t believe in bans at all. “I don’t follow the banned books list because I think it’s all nonsense,” said Martina Abrahams Ilunga, a user-turned-volunteer at The Free Black Women’s Library. “These books often make people afraid because they give people the tools in helping us claim our own power.”

Helmick said that local initiatives like The Free Black Women’s Library play an essential role in preserving access to information, enabling a part of the next generation to have uncomfortable conversations that arise from conflict of opinions and beliefs.

“It’s like the books aren’t banned in my life,” said Abrahams Ilunga. “They’re not banned in my community, or in my heart.”

Written and reported by Muskaan Darshan