Patrick McCarver hasn’t forgotten the summer evening when his friend’s wife winced in pain every time she talked and needed numbing medicine for her sore tongue. Every pharmacy within walking distance was closed for the night, and there were no 24-hour options. So, McCarver and his friend had to ride the G-line to Clinton Hill to get a prescription.

Nationwide, pharmacy chains are closing, creating pharmacy deserts. When Rite-Aid filed for bankruptcy this summer and closed all its Brooklyn locations, Bedford Stuyvesant lost one of its three big pharmacies with long, flexible hours.

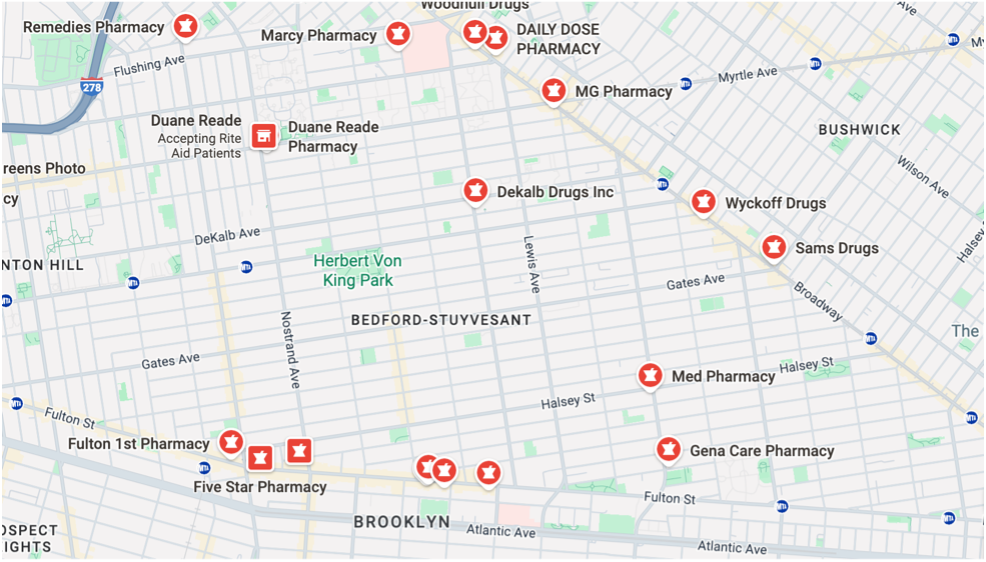

But Bed-Stuy does not qualify as a pharmacy desert. The neighborhood still has more than 15 small, independent pharmacies. Even so, some residents say that these pharmacies are unevenly distributed, have limited hours and often run out of items – highlighting a gap between how pharmacy access is measures and how it is experienced.

McCarver, who has lived in Bed-Stuy for about eight years, considers himself fortunate to live close to a local pharmacy. “I think that I got really lucky, but occasionally they won’t be able to stock, and I will have to go really far,” he said.

For Carlos Holz though, “pharmacies are a problem. We don’t have any pharmacies close by where we live.” He said he buys medications “when I am in other neighborhoods, and I see some pharmacies there.”

A 2024 study showed that Queens, the Bronx, Brooklyn and Staten Island had 86% fewer pharmacies compared to Manhattan – with only six pharmacies per 100,000 residents, compared to Manhattan’s 43.

According to a division of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 90% of urban residents should have a pharmacy within two miles, which Bed-Stuy does.

But Jessica Satterfield, the Associate Director of Policy and Pharmacy Affairs at the National Community Pharmacists Association, said that the centers’ standards are outdated and no longer ensure necessary access.

“When you consider circumstances like people who have trouble walking and don’t have transportation, the one mile to and from a pharmacy in an urban area becomes more daunting,” Satterfield said.

Some local pharmacists agree that they might not always be open, but note that they provide critical connection with their customers. “People prefer coming here more than Walgreens because we know them, we care about them and their families,” said Alex Keen, a local pharmacist at Five Star Pharmacy. “Most people understand that we don’t give service all the time. Even the Walgreens across the street doesn’t.”

Independent pharmacies have been shown to play a vital role in ensuring equity in pharmacy access because older adults and low-income households rely on them more than on chain pharmacies, according to a 2023 study in Health Affairs Scholar.

Local pharmacies are also quicker, due to shorter queues in-store. Inna Rutkovska, a pharmacist at Health Plus Pharmacy, said that Urgent Care prefers to work with the local businesses over chains because when patients need medication urgently, local pharmacies can provide it within 10 minutes.

Even as the chains close, local pharmacies are struggling financially. Satterfield said that falling reimbursements to independent pharmacies are tied to pharmacy benefit managers, which act as intermediaries between health insurers and pharmacies. They negotiate reimbursement rates, and have been linked to mounting financial pressure on independent pharmacies.

Rana Uzman, a pharmacy technician at Gates and Garvey Pharmacy, said that they usually end up filling prescriptions out of the pharmacy’s own money because some insurance companies delay reimbursement or barely cover the costs of the medications. Nevertheless, these independent pharmacies keep serving their communities.

Uzman said he cannot turn patients away when they need medication, regardless of the challenges.

Muskaan Darshan

6th October 2025